It’s impossible for any team to completely eliminate injuries from their squad, as the very nature of sports dictates that there will always be uncontrollable factors that lead to athletes getting hurt. But by combining the expertise of a committed performance staff and information collated in an athlete management system (AMS), the risk of preventable incidents can be reduced.

To better mitigate injuries, closer collaboration and clearer communication is needed across the club or organization. This will help provide more data that will improve injury prediction models and algorithms, which are currently unreliable.

Creating Standard Operating Procedures Across the Organization

For injury risk profiling to have a positive impact, it needs to become woven into the fabric of the organization. This means everyone accepts the part it will play in decision-making, agrees on terminology, and understands what their role will be in collecting, collating, and applying data to minimize injury rates.

Speaking in a panel discussion for the Vanguard Roundtable podcast, Garrett Bullock, assistant professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine, asserted that integrating injury risk into the culture starts at the top. “You need to have a discussion with the manager, head coach, or commander and hone your message toward the main stakeholders,” he said. “There also needs to be standard operating procedures with standardized language in a glossary, and the information should be presented to suit different learning styles.”[1]

Injury risk profiling cannot be isolated to one area of expertise, such as medical, sports, science, or strength and conditioning. Performance staff need to work hand-in-hand with S+C professionals and the coaching team to closely monitor acute-to-chronic workload ratios and ensure that athletes aren’t being exposed to large jumps in volume or intensity. Such spikes can overload players’ bodies and predispose them to injury.

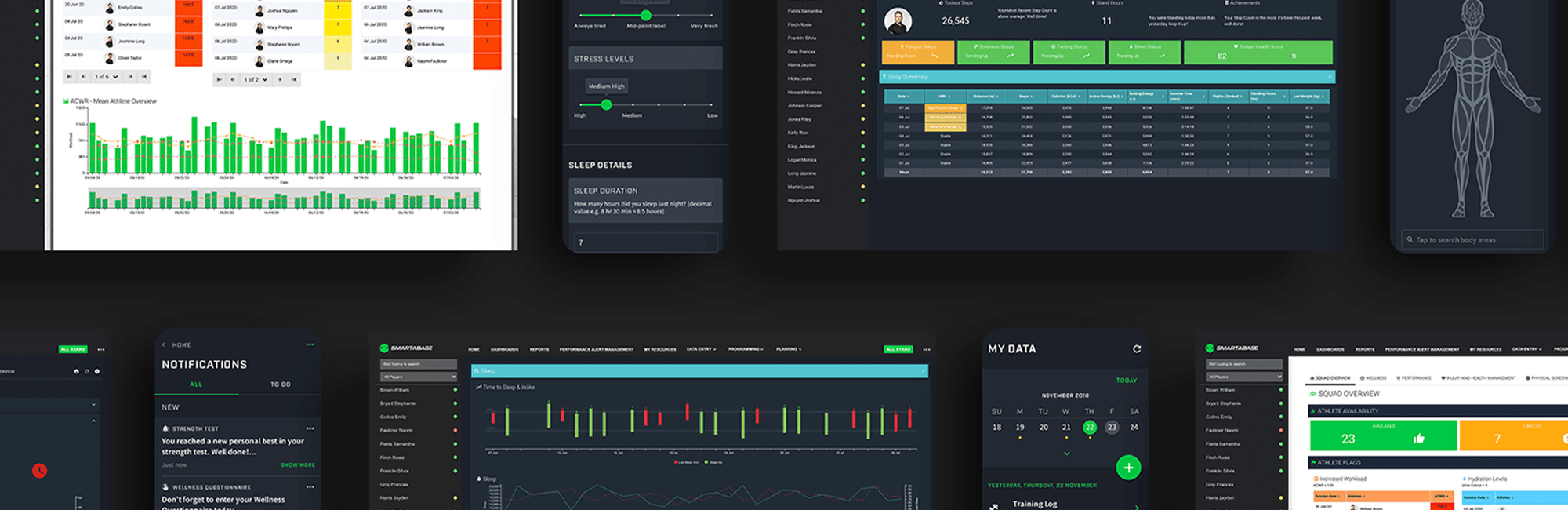

Utilizing an athlete management system (AMS) such as Smartabase can help professionals throughout the performance staff to closely monitor internal and external loads that players are subjected to in the weight room, during practice, and in games so that they aren’t being overloaded to the point of increasing injury risk.

When dealing with return-to-play protocols for injured athletes, the conversation should include team doctors, athletic trainers, physical therapists, and others responsible for quarterbacking care during various stages of the rehab process. When they work together, this cross-discipline team can help ensure the athlete is exposed to adequate training stimuli to build the load tolerance needed for getting back into practices and competitive play, without overdoing it and causing a setback or increasing the likelihood of re-injury.

Taking Lifestyle Factors into Account

An AMS can also collate sleep and recovery data from wearables so that if anyone is under-recovering, this can be flagged via the AMS and the appropriate steps taken to better educate them on how to bounce back between training sessions and games.

There’s a bevy of research to demonstrate that getting insufficient sleep increases athletes’ injury risk. For example, the authors of a review published in Current Sports Medicine Reports wrote that “The amount of sleep that consistently has been found to be associated with increased risk of injury is ≤7 h of sleep, which when sustained for periods of at least 14 d has been associated with 1.7 times greater risk of musculoskeletal injury.”[2]

An AMS can automatically alert members of the medical, performance, and coaching staff when an athlete is consistently sleeping poorly, so they can correct the individual’s sleep pattern before it puts them at greater risk of injury. The same goes for self-reported surveys that indicate when individuals aren’t feeling well rested or are reporting higher RPE (rate of perceived exertion) scores than normal for training sessions – both of which could indicate fatigue and inadequate recovery that elevate their chances of getting hurt.

Informing Programming, Movement Correctives, and Risk Management

Such a collaborative group can also come together to reduce the likelihood of athletes or warfighters getting hurt in the first place. An AMS like Smartabase can be used to manage results from predictive assessments such as the Functional Movement Screen (FMS), which is widely used across professional and college sports and the military.

A meta-analysis of studies vetted the effectiveness of the FMS as shown by 14 prior studies. Writing in the American Journal of Sports Medicine, the authors concluded: “Participants with composite scores of ≤14 had a significantly higher likelihood of an injury compared with those with higher scores, demonstrating the injury predictive value of the test.”[3]

Once every squad or unit member has been taken through the FMS by an athletic trainer, the scores could be made available to the rest of the training staff, physicians, sports scientists, and strength and conditioning coaches via the AMS. Any individual with a low score (14 or less) could be automatically flagged. The performance staff would then work together to administer corrective exercises that fix dysfunctional movement patterns, re-test to see if movement scores improve, and take any other measures that the group decides is needed to intervene before the high-risk group actually starts getting hurt.

During the Vanguard Roundtable discussion, Darin Peterson, human performance director at the US Marine Corps School of Infantry East, gave a specific example of how the findings of injury prediction tools – whether they’re analog assessments like the FMS or more high-tech ones that utilize machine learning and algorithm-based analysis – can best be utilized by performance staff. “Injury risk predictability helps us more with programming,” he said. “For example, the posterior chain tends to be pretty weak in our military. So we know we need to always work on increasing posterior chain strength and power production. That’s more valuable than us saying to a member, ‘You’re more likely to get injured in this type of setting or in this location on your body,’ which can create a mindset that throws them off.”

Rather than expecting an automated system to provide the precise prediction of a certain type of injury on a specific day – such as player X is going to tear their ACL on Thursday – organizations should use injury mitigation models as merely another tool in their risk assessment toolbox as part of a collaborative process between subject matter experts. “Risk management is something these tools can be used for,” Bullock said. “I think we can do a better job of shared decision-making when dealing with a higher risk of injury. When there’s closer collaboration between the strength coach, PT, MD, and other stakeholders, I think that could help actually use the models the way they really should be used.”

With movement assessment scores, load monitoring data, wellness surveys, sleep scores, and more at their fingertips in an AMS, a performance group that’s collaborating effectively might not even need to use separate injury modeling software, which frequently fails to live up to its billing. In a paper published in Sports Medicine, a research team led by Bullock stated that too many of these systems “cannot aid in interpretation, or guide intervention” because their injury risk models are proprietary and have not been subjected to rigorous, peer-reviewed analysis.[4]

Removing Siloes and Enhancing Cross-Discipline Communication

The efficacy of injury risk profiling will always remain limited if each domain within the human performance staff is a self-contained unit. Data collection needs to happen in the training room, during practice, in the weight room, and in other settings across the facility so that it can be fed back into a centralized platform and inform injury models and algorithms. The greater the buy-in from the entire staff, the more robust the collected data sets will be and, assuming the right technology is being used, the more reliable the resulting predictions and risk analyses will become.

One of the hallmarks of impactful collaboration in both sports and the military is effective and clear communication. In the roundtable discussion mentioned earlier, Peterson shared what his years of leadership experience in the Marine Corps’ human performance group suggests about the best way to get everyone on board with a proactive approach to injury management: “In order to get these types of risk profiles going, the organizer has to have athletic trainers talk to strength coaches, strength coaches talk to orthopedics, and orthopedics talk to behavioral health specialists,” he said. “All the different entities must come together and have these conversations when you’re in the organizing stage. Everybody’s got to be entering data into the same system so that it’s not siloed.”

Bullock also believes that injury risk profiling will only be useful and effective if the insights gleaned from the data are shared in a way that can be easily comprehended and made actionable throughout the organization. “Make sure that your stakeholders – the soldier, athlete, coaching staff, and so on – understand what you’re trying to communicate to them,” he said during the Fusion Sport panel talk. “Communication is key. You could have the best algorithm and the best tech in the world, but if people don’t understand it, then it doesn’t mean anything.”

If You Enjoyed This Article, You Might Also Like…

- PODCAST: The Promises and Pitfalls of Injury Prediction

- Six Reasons to Integrate Your AMS + EMR

- Smartabase for the NBA: Injury Risk Profile

- Human Performance Optimization Tech Stack 2022

[1] “The Promise and Pitfalls of Injury Prediction,” Vanguard Roundtable, April 5, 2022, available online at https://fusionsport.com/blog/vanguard-roundtable-promise-and-pitfalls-of-injury-prediction/.

[2] Kevin Huang and Joseph Ihm, “Sleep and Injury Risk,” Current Sports Medicine Reports, June 2021, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34099605.

[3] Nicholas A Bonazza et al, “Reliability, Validity, and Injury Predictive Value of the Functional Movement Screen: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” American Journal of Sports Medicine, March 2017, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27159297.

[4] Garrett S Bullock et al, “Black Box Prediction Methods in Sports Medicine Deserve a Red Card for Reckless Practice: A Change of Tactics is Needed to Advance Athlete Care,” Sports Medicine, February 17, 2022, available online at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-022-01655-6.