Playing sports often provides a sense of self-efficacy and makes participants feel confident and capable, not to mention the various physical benefits of being fit and healthy. And yet the intersection of performance, society, and popular culture can create unrealistic expectations of what an ideal competitor should look like, while there is added pressure within certain sports for athletes to keep their weight low. In this article, we’ll explore how these factors characterize a toxic diet culture that causes body image issues, disordered eating habits, and mental health challenges, and suggest some ways coaches and organizations can help their athletes tackle such problems.

A position statement from the Australian Institute of Sport stated that both disordered eating (DE) and clinical eating disorders (EDs) are more common in sports than many people might think, and that the incidence of both is greater in certain disciplines. “Overall, there is a higher prevalence of DE and EDs in athletes compared with non-athletes. Additionally, athletes participating in aesthetic, gravitational and weight-class sports are at higher risk of DE and EDs than those in sports without these characteristics.”[1] In a recent episode of The Vanguard Roundtable podcast, several experts discussed how these issues and other diet culture-related ramifications are impacting student-athletes, and what a collegiate performance staff can do to help.

“It’s about embracing body diversity, not making assumptions about body weight, shape, and size, or pressuring athletes to be a certain way and not eat certain foods,” said Rachel Manor, sports performance and eating disorder dietitian with Lutz, Alexander and Associates Nutrition Therapy. “Also not using diet culture phrases because they perpetuate negative body image and can lead to disconnected eating. Instead, performance professionals can promote an ‘all foods fit’ approach, understand that all bodies are good bodies, and that elite athletes come in a variety of shapes and sizes.”

Encouraging Intuitive Eating

Despite the name, diet culture doesn’t merely mean following a certain eating approach. It can include this but is, broadly speaking, the glorification of being thin and having a low body weight. This leads to the stigmatization of different body types that don’t fit stereotypes, labeling certain foods good or bad, and turning nutrition selections into moral choices. The pervasiveness of diet culture is tricky enough for the general population to deal with, but for athletes, it can be even more problematic, as faulty norms celebrate a body image that can be at odds with performance and overall well-being and might cause or contribute to dysfunctional eating habits and mental health struggles.

Fortunately, coaches and other staff have the opportunity to dismantle the destructive diet culture narrative and replace it with truths about how athletes need to fuel for their sport instead of aesthetics and taking a more balanced approach to nutrition. One way to do so is to eat intuitively instead of restrictively.

“Intuitive eating is this dynamic interplay of instinct, emotion, and rational thought,” Manor said during the roundtable discussion. “It’s a framework of learning how to eat for self-care, reject the diet mentality, practice body attunements guided by hunger and fullness, have respect for our body, and challenge the food police. Mental health is impacted by people’s food and body image, so intuitive eating really addresses that.”

Finding Teaching Moments and Taking a Multidisciplinary Approach

Social and traditional media can often perpetuate diet culture, with the former also being the source of online bullying and body shaming. Yet if athletes can find the right examples, they can also discover positive role models, creative ideas around nutrition, and affirming support for their own journey. Even if they stumble upon fads, such content can serve as a conversation starter with their coaches, who show how a certain approach could be beneficial or, if it isn’t, present better alternatives.

“We had a big issue when there was a Netflix documentary that came out a few years ago, and our entire cross-country team wanted to switch diets in the middle of the season,” said Taylor Lipinsky, associate athletic trainer for the University of Cincinnati women’s basketball team, in The Vanguard Roundtable episode. “I said we should go talk to our dietician. Before we have this discussion and just decide we’re going to change all these things, let’s make sure we’ve talked to the proper professional to integrate these things into your life if that’s what you decide to do.”

If an athletic department unites around combating diet culture, they will have the opportunity to assemble a well-rounded group of subject matter experts who can better inform student-athletes about how to prepare and fuel their bodies. “It is definitely a team approach, making sure we have a medical doctor in the mix with the athletic trainer, a mental health professional, and one of our dietitians,” Lipinsky said. “Such a multidisciplinary strategy should acknowledge and validate the issues that people might be struggling with and present an alternative, more constructive narrative that begins to override the false messages of popular culture.”

Such an initiative can be even more effective if upperclassmen and women can collaborate with the performance staff and take an active leadership role in promoting a healthier approach to nutrition and body image. “Veteran athletes and captains can have an incredible influence on their team,” Manor said. “If they can take a stand against diet culture, promote intuitive eating, and prioritize athletes getting their needs met, that positive peer pressure can be really helpful. As much as sports psychologists, dieticians, and athletic trainers can give athletes education around the importance of positive body image and optimal nutrition, peer influence is just so valuable.”

Serving the Entire Student-Athlete Population

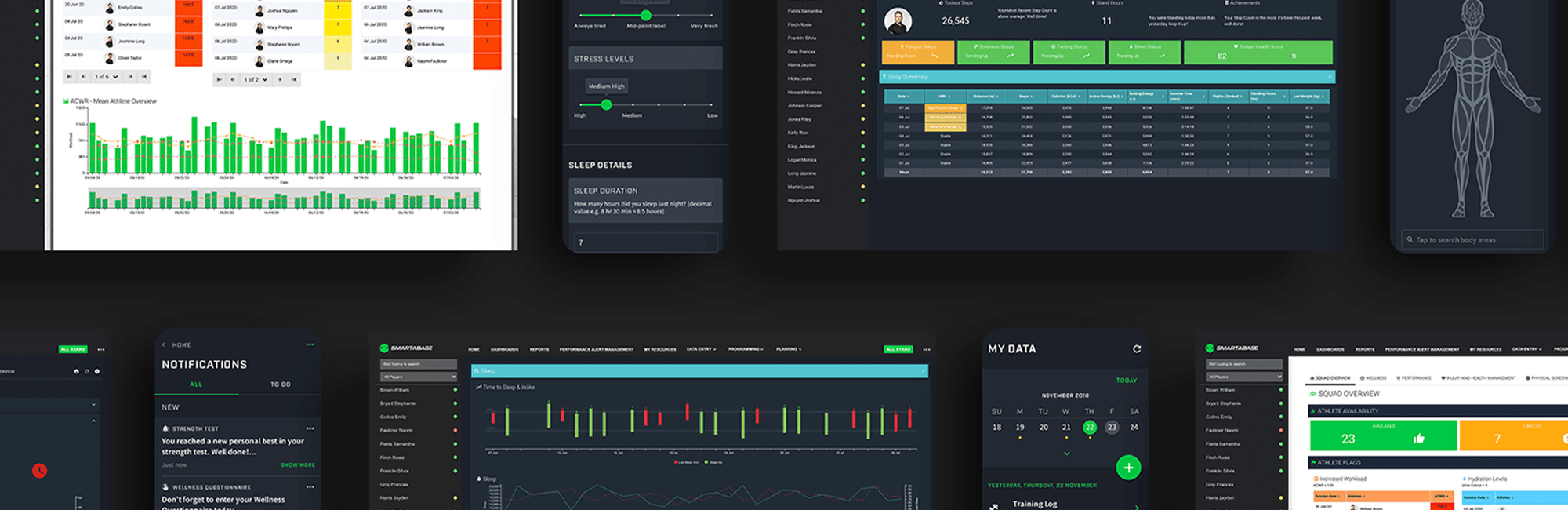

Collecting data in an athlete management system like Smartabase and presenting it to athletes can help provide more objective guidance around nutritional goals if it’s done in a simple, informative, and considerate way. “If you use things like Bod Pods and other measurements like that, it’s very important to be open with the student-athletes about how you’re using it and why you’re doing those things.” Lipinsky said.

“Keep in mind who you’re working with when you deliver this information,” added Lenecia Nickell, director of sports psychology and wellness at the University of Cincinnati. “Consider the individual and make sure you’re not using overly clinical language with folks who might not be there yet. What we’re looking for is optimal – what’s going to get you performing at your best level. Let’s get some very specific definitions and small, measurable goals, as we’re trying not to overwhelm people with change.”

One of the challenges facing athletic departments when it comes to educating student-athletes on body image, nutrition, and diet culture is that the physical demands of each sport can vary greatly. Smartabase consultant and Vanguard Roundtable host Emma Ostermann gave the example of a football player using the same dining hall as a female gymnast and asked the panelists how they’d help meet their differing needs.

“Nutrition is very individualized and so hopefully, the football player has connected with his support team and is feeling competent and empowered to get his needs met and the gymnast is also,” Manor replied. “I hope they’re both optimizing their energy availability, getting enough carbohydrates, fats, and proteins to be able to perform, and they’re not engaging in any kind of restrictive, restrained, or limited way of eating, regardless of the sport that they’re playing.”

Bringing Joy Back to Eating and Taking a Long-Term View

Nutrition can become a source of stress, anxiety, and worry for some student-athletes that escalates into restricting or avoiding certain foods, developing eating disorders, and having a distorted body image. To start reframing this thorny topic, the performance team needs to begin destigmatizing food, removing “good” and “bad” labeling, and “incorporating an individual student-athlete’s cultural background into intuitive eating,” Nickell suggested.

Emphasizing the social aspects of sharing a meal with teammates and treating food as a means of celebration rather than denial can also start to override the notion that student-athletes should become robots who are only concerned with what the scale tells them and need to constantly obsess over calories and macronutrient intake. “Food is more than fuel – it’s connection and tradition,” Manor said.

In addition to ensuring that student-athletes are educated about the nutritional needs of optimal performance in their particular sport and for their body type, staff can also broaden their view beyond what takes place during their college career. Certainly, helping individual athletes and teams maximize their athletic potential on the field or court is important, but it should be just as significant for the athletic department to equip them with the tools needed to live a healthy life long after they graduate. Doing so begins by taking aim at the mistruths of diet culture and sharing a better definition of true health and wellbeing.

“Another thing that I’ve approached with some of my student-athletes is their long-term health, in terms of the decisions that they’re making and body image,” Nickell said during the podcast discussion. “There will come a time when your definition of healthy is going to change, so what’s sustainable for your body type and size?”

Fueling for Optimal Performance and Wellbeing

Researchers from Oklahoma State University investigated whether female collegiate athletes were meeting current sports nutrition standards and found that “the energy and carbohydrate intakes were below the minimum recommended amount, with only 9% of the participants meeting their energy needs. Seventy-five percent of the participants failed to consume the minimum amount of carbohydrates that is required to support training. The majority of the participants reported no regular breakfast, 36% consumed <5 meals/day, and only 16% monitored their hydration status.”[2]

While the authors didn’t comment on whether diet culture was partly responsible for the delta between what female athletes need to be consuming to support training and recovery and what they’re actually eating, it’s likely that it was a contributing factor. “When you’re thinking about female athletes, there are two worlds that they can live in – depending on the sport – of being a very strong competitor and the body image and style that goes with that, versus what society deems acceptable or valued in terms of the female body,” Nickell said in the roundtable discussion. “Those two things can really be at war with each other.”

There could also be a lack of fundamental education among student-athletes about what the energy and macronutrient needs of collegiate sports are, which creates an opportunity for staff to step in and teach about this in the context of a holistic approach to eating.

“When an athlete is led to believe that their body needs to look a certain way in order to optimize their performance, they feel like they need to be really strict or rigid, or cut out things or food groups,” Manor said during the podcast. “I try to provide education around diet culture, and how that has influenced their thoughts and feelings about their food and bodies. In my clinical practice, we incorporate the science of sports nutrition with the intuitive eating framework and learning how to eat for self-care – I think that’s where the magic happens.”

If You Enjoyed This Article, You Might Also Like…

- PODCAST: Body Image & Performance for Collegiate Student-Athletes

- PODCAST: Body Comp Testing

- How to Effectively Share Performance Info with Athletes

- Considering the Whole Person Versus Treating Individual Injuries

- The Growing Influence of Athletes and the Impact on Human Performance Data

[1] Kimberley R Wells et al, “The Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) and National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) Position Statement on Disordered Eating in High Performance Sport,” British Journal of Sports Medicine, November 2020, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32661127.

[2] Lenka H Shriver et al, “Dietary intakes and Eating Habits of College Athletes: Are Female College Athletes Following the Current Sports Nutrition Standards?” Journal of American College Health, 2013, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23305540.

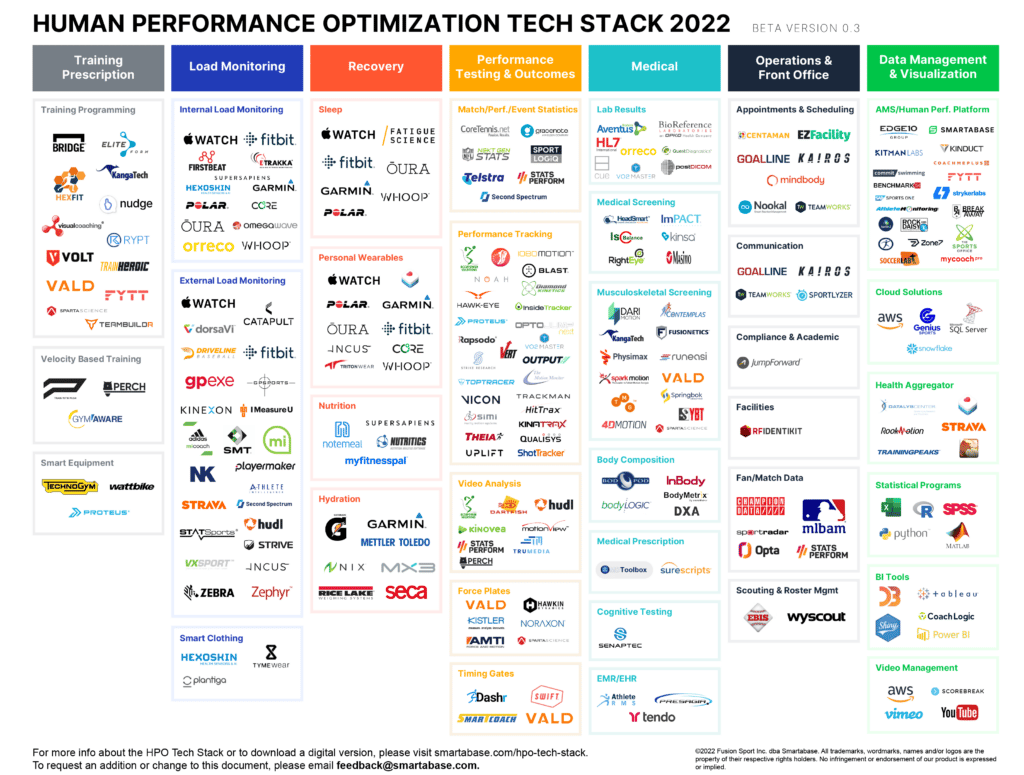

Fortunately, certain tools can help the data and analytics team get up to speed quicker. For example, rather than wasting time trying to extract data stored in many different silos (such as databases, spreadsheets, and vendors’ proprietary systems), it can be united in a single platform with an athlete management system (AMS) such as Smartabase. This can bring together GPS metrics from practice, game stats, performance testing, physical screening, and many other types of information, making it easier to grasp all the data the organization collects.

Furthermore, Smartabase offers out-of-the-box integrations such as the Analytics Connector which provides an efficient solution for continuously transferring and synchronizing all your Smartabase data to your database (MsSQL, MySQL, PostgreSQL, or Redshift). Once this has been achieved, you can use your preferred scripting language (R, Python, etc.) or BI tool (Power BI, Tableau, etc.) to query this data. If you do not have access to or want to maintain an external database, you could still pull data directly from Smartabase into your preferred R environment using the R Connector. This is a library for R that allows you to export/import data from and into Smartabase using a minimal amount of code.

Tiered Hiring Strategy

When it comes to deciding who to hire first for your data and analytics team, there is not a single strategy that would ensure a 100% success rate. Instead, it depends on several factors, such as: What kind of projects will your team work on? How easily available is the data in your organization? What is your hiring budget? What is your organization data maturity level?

Learning about the `Data Science Pyramid of Needs` framework, introduced by Monica Rogati in 2017, is key to understanding why you should prioritize hiring for some roles before others. This framework not only lists the stages of the Data Science process, but also explains why it is not possible to advance further in the process without fulfilling all the previous stages. But what does this really mean?

Organizations turn to data scientists to build forward-looking predictive models to give them an edge against their competitors in areas such as talent identification, recruitment, etc. In the Data Science Pyramid of Needs, this type of work (testing, modeling, and research) sits at the top of the pyramid. What often gets overlooked is that the accuracy of a prediction model largely relies on the availability of abundant and reliable historical data; an area where data analysts play a key role – this is the middle part of the pyramid. Lastly, the job of the data analyst could not be possible if there were no systems and processes in place to capture, store, and make the data available for analysis in the first place, which is the responsibility of data engineers.

By now, you probably realize the importance of understanding this framework when deciding who you should hire first. Does this mean you need to hire a Data Engineer first? Not necessarily. If your organization is already leveraging an AMS like Smartabase that brings a vast array of data sources into one system and it allows you to query this data using your preferred analytics IDE or BI tool, your data analyst or data scientist will dedicate most of their time building reports or predictive models (and bringing value to your organization), rather than struggling to access the raw data.

Creating a Blueprint for Smaller HP Analytics Teams

Even in countries that are leading the charge in human performance like Australia, the resources allocated to establish new data and analytics teams can often be limited. If this is the case in your organization, hiring a ‘generalist’ data and analytics professional who can leverage some knowledge about infrastructure (AWS, Azure, etc.), ETL tools (Fivetran, Airbyte, etc.), programming (SQL, R, Python, etc.), and visualization tools (Power BI, Tableau, etc.) would make sense. They will be able to set the foundation to build on and provide some early return on investment that could trigger the further growth of the team.

Remember to create the right environment for your team members to engage with HP domain experts and learn about their problems. If you have limited resources, try to focus on a small number of highly targeted projects that can portrait the value your team can bring to the organization. This is a great blueprint for any HP analytics team to follow in its early days: combine technical expertise with domain knowledge, turn performance problems into data ones, and then master one or two specific areas. This will allow you to find easy wins that demonstrate the true value of data analytics to the rest of the organization and get buy-in from coaches and others who can become advocates for your HP program moving forward. Such victories do not have to involve fancy techniques or sophisticated models but can be as simple as getting people the data they need, when they need it, in a format they can use.

If You Enjoyed This Article, You Might Also Like…

- GUIDE: Building Your Human Performance Analytics Team

- How US Ski & Snowboard Built an Analytics Team to Support High Performance

- Should You Outsource Your Human Performance Analytics Team?

- Using Archetypal Analysis for Team Training, Selection, and Cohesion

- Tips for Integrating Your Human Performance Platform with Analytics Tools