It’s challenging enough for performance, medical, and coaching practitioners to oversee athletes in a single sport. So when a team is responsible for the wellbeing of athletes involved in multiple disciplines or even different sports, the level of difficulty increases exponentially. Then add in the pressure of delivering results at the most prestigious event – the Olympics – and it’s clear that national federations, institutes, and Olympic committees have their work cut out for them. In this article, we’ll look at the unique hurdles such organizations face as they try to keep their athletes healthy and examine how technology is helping.

THE UNIQUE DEMANDS OF A FOUR-YEAR CYCLE

Maintaining athlete durability over the course of a single season is a tough task, particularly at the professional level. Yet it pales in comparison to the task of doing the same for prospective Olympians throughout the atypically long four-year training cycle. Elite soccer, rugby, and basketball players have relatively short offseason and preseason periods compared to the length of their competitive calendars, when they must perform up to three times a week for between 38 (Premier League soccer) and 162 (Major League Baseball) games. Whereas for Olympic athletes, the bulk of the quadrennial period is spent building up for an event four years in the future that might be over in a matter of seconds.

From a performance perspective, the quadrennial cycle also makes it tricky to effectively implement a training approach that will subject each athlete to enough of a consistent stimulus to prompt the desired adaptations without pushing them too far into overtraining and injury. For organizations that manage multiple sports and disciplines, this is even more complex due to the differing demands of athletes’ competitive schedules. These can vary dramatically based on events sanctioned by national bodies like USA Weightlifting and international entities such as the IAAF.

Even in sports that only receive widespread attention and acclaim during the Olympics, athletes will likely be called upon to compete for their country periodically. Examples include world and European championships and the Commonwealth and Pan-Am Games. Some sports like track and field may also have extensive indoor and outdoor race seasons (COVID-19 disruptions notwithstanding) that place additional load on athletes that might increase their likelihood of injury. This doesn’t only apply to the rigors of practice and competition, but also to factors like sleep disruption and travel-related stress.

In sports like downhill skiing or snowboarding, the competitive calendar can be season or weather-dependent, while in others like tennis, the circuit runs almost year-round, with players traveling all over the world to play in minor, midlevel, and major tournaments regardless of where they may fall in the Olympic cycle. As such, some athletes might report for national team duty already worn down, dinged- up, and depleted, and then be asked to put on their nation’s uniform and compete for a spot on the podium.

Olympic teams in the United States always feature some athletes who are still competing in college sports. In any Olympic cycle, this adds a wrinkle to national team preparations, as runners, swimmers, and other competitors try to balance the demands of intercollegiate athletics, academics, and playing for Team USA. Due to seasons shifting, being shortened, or getting canceled because of the pandemic (more on this in a moment), it’s arguably harder than ever for performance staff to manage the college athletes who’ve earned a Team USA spot at the Tokyo Games.

THE RAMIFICATIONS OF ADDING A FIFTH YEAR

This particular Olympic cycle has presented a unique challenge to performance, coaching, and medical staff: the quadrennial was extended by a year because of COVID-19. Though the organizing committee of the Tokyo Games and the IOC were initially adamant that there would be no postponement, the rapid spread of the virus soon made this inevitable. Suddenly, all those athletes and their support staffs who had circled July and August 2020 on their calendars had to cross that out and set a new target for the same dates in 2021.

This forced everyone involved to not only defer their goals by 12 months, but also extend training cycles and write new periodized plans that took the revised schedule into account while also considering training intensity distribution (see this study to learn how two rowers’ training was spread across an entire Olympic cycle).[1] For injured athletes who were struggling to return to competition in time for the summer 2020 Games, this extension provided a welcome reprieve and the opportunity to heal up without having to rush their recovery and risk potential re-injury. However for others, the extra year of training is exposing them to more acute and chronic load. For athletes with high catastrophic injury rates like boxers, martial artists, and gymnasts and those more likely to suffer from volume and mileage-related maladies like runners, cyclists, and rowers, the delay of the Tokyo Games has raised the stakes.

MANAGING ATHLETES IN DEMONSTRATION SPORTS

Olympic committees, institutes, and national federations also face unique challenges when trying to manage the training and competitive loads of athletes who will be competing at the Tokyo Games in one of six demonstration sports: baseball, softball, surfing, skateboarding, karate, and climbing. The first two on this list will require national teams to coordinate their efforts with players’ pro franchises, which will understandably be concerned about having their most prized assets competing on the world stage. The benefit here is that many baseball and softball teams already collect, collate, and manage extensive performance and health data on their players that can, at least in theory, be shared with institutes, committees, and federations to help them safeguard athlete wellbeing in the runup to the Tokyo Olympics.

This isn’t the case with surfing, skateboarding, and climbing. While the first two on this list have international circuits, their athletes typically have far less structure than Olympic sports like weightlifting or rowing. Some competitors might train together on occasion, but they’re typically reliant on individual specialists and largely responsible for their own training. Similarly, climbing does have some national and international contests, but climbers usually prepare alone both indoors and outdoors. They’re certainly not used to having a governing body overseeing their training or preparation or competing at an event the size and scope of the Olympics.

The inaugural Olympic climbing event is also throwing competitors a curveball by combining elements of sport and speed climbing that are usually separate. While there are a handful of athletes who are proficient in both, most are specialists who must now expand their skillset to have a hope of medaling in Tokyo. As such, they will be increasing their training load and potentially their injury risk. The same is true of any Olympic event that will require athletes to participate in a format or over a distance that is different to what they’re used to in regular competition, such as Ironman athletes downshifting to the Olympic triathlon course that consists of a 1,500-metre swim, 40km bike ride, and 10km run.

USING DATA-DRIVEN INSIGHTS TO REDUCE OLYMPIANS’ INJURY RISK

Sports performance and medical practitioners are always going to have an instinctive sense when something is not right with an athlete and changes need to be made to their programming to prevent injury. The same goes for a master-level coach who sees his or her player lagging when they’d normally still be going strong and decides to pull them out. But as crucial as situational awareness derived from years of expertise is, it can be even more potent when combined with strategically selected data that’s delivered in the right way.

According to the authors of a study about monitoring multisport and multidiscipline athletes that was published in The BMJ, “Standardised injury surveillance provides not only important epidemiological information, but also directions for injury prevention, and the opportunity for monitoring long-term changes in the frequency and circumstances of injury.”[2]

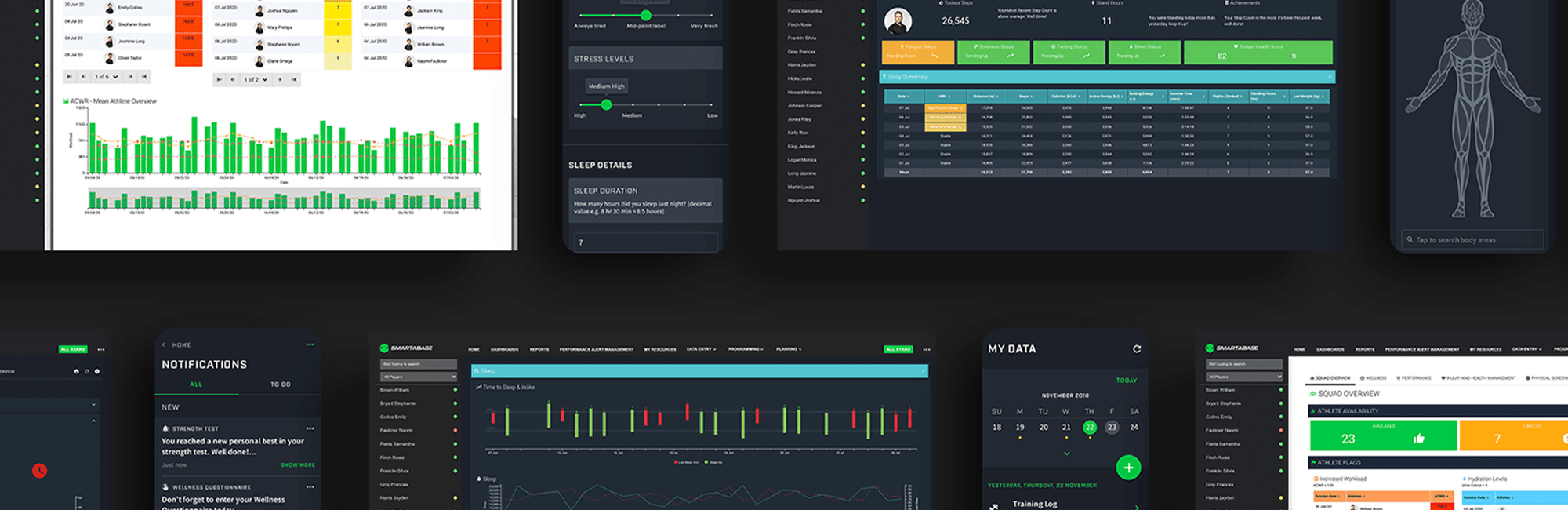

Since 2013, the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) has been using the Smartabase athlete management system to achieve such standardization across all the sports that it oversees. Gathering and interpreting real-time and historical athlete data from seven sites around the country where national team athletes train helps optimize preparation for the Olympics and other international competitions for senior team and age-group athletes alike.

It’s not the sheer number of data points accumulated – three billion and counting – that’s most significant, but rather the quality of the decision-making that this information allows. Whether it’s a head or assistant coach, a strength and conditioning specialist, or a team doctor, everyone on the support staff now has access to the same data, which creates a common language, keeps communication current, and ensures a cohesive approach to managing each athlete’s status.

By creating a truly centralized national system, AIS has been able to improve the performance of Australia’s Olympians and mitigate their risk of injury. Across all sports, the AIS has seen a reduction in injury rate of 30 to 40 percent, with some squads reducing that number by up to 90 percent. The value of using an athlete management system isn’t just for preempting injury, but also being able to respond quickly and effectively in coordinating a player’s return to training and competition if they do get hurt.

THE IMPACT OF IMPROVED INJURY AND ILLNESS MONITORING

U.S. Ski & Snowboard is another national team that has improved its injury surveillance by effectively combining performance and medical data for athletes in seven sports in a single, unified platform. This includes using Smartabase as both a performance data management and electronic medical records (EMR) platform. This unified approach allows staff to monitor the preparation and progress of each athlete on an individual basis and also to quickly generate reports by injury type (such as ACL tears) and/or discipline (like free or downhill skiing).

The organization utilizes this system to collect and analyze data that helps correlate training load with injury from training and competing overseas and ensured that the correct protocols have been followed afterward. Since starting to use Smartabase, U.S. Ski & Snowboard has seen a significant decline in knee injuries, which it attributes to better athlete preparation and monitoring. This shows the validity of a data-driven methodology that a paper published in Frontiers in Sports and Active Living recommended as part of a more collaborative approach to sports injury prevention and rehabilitation.[3]

When the Tokyo Olympics come around, the casual fan watching on TV will see the culmination of five years’ preparation manifesting itself in a few minutes of mastery on their screen. Behind the scenes, a new wave of data collection, aggregation, and analysis tools are the secret weapons that empower these athletes to stay healthy so they can perform their best when it matters most.

Smartabase is used by Olympic Committees, Institutes and National Federations around the globe for injury prevention by seamlessly connecting their performance and medical data.

[1] Daniel J Plews and Paul Laursen, “Training Intensity Distribution Over a Four-Year Cycle in Olympic Champion Rowers: Different Roads Lead to Rio,” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, September 2017, available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320073476_Training_Intensity_Distribution_Over_a_Four-Year_Cycle_in_Olympic_Champion_Rowers_Different_Roads_Lead_to_Rio

[2] A Junge et al, “Injury Surveillance in Multi-Sport Events: The International Olympic Committee Approach,” The BMJ, June 2008, available online at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18390916/.

[3] Pascal Edouard and Kevin R Ford, “Great Challenges Toward Sports Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation,” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, July 3, 2020, available online at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspor.2020.00080/full.